CROMWELL’S HEAD

THE HISS-TORY BEHIND THE HISSING

Oliver Cromwell is the only uncrowned head of state that England has ever known. He emerged as the victor in the bitter English Civil War of 1642-1651, saw to it that his defeated rival, King Charles, was publicly beheaded and then ruled the country as Lord Protector for the next nine years. He was a pious, self-righteous, brutal man who used his power to shape society according to his own austere, puritanical Christian beliefs: the alehouses were shut, the theatres closed and even the celebration of Christmas was declared illegal.

As he lay dying of the ague (a kind of malaria) in September 1658, he might have imagined that he would leave a glorious legacy, that he would be remembered as one of the nation’s greatest leaders. And in many ways, he has been. His statue stands in pride of place outside the Houses of Parliament in Westminster. The classic biography of him by Antonia Fraser is sub-titled ‘Our Chief of Men’. He still regularly makes it into the lists of greatest-ever Britons.

Which is why what happened to his head is so extraordinary. In the story The Hissing of Oliver’s Head, one of the characters gives a brief summary but I thought I’d take the opportunity here to flesh it out a bit… just in case you’re interested.

Cromwell was buried with all the

pomp and splendour befitting a head of state in Westminster Abbey, the

traditional resting place of England’s kings and queens. And it was generally assumed

that he would be succeeded by his son, Richard, as the ruler of the nation.

But Richard was better known by his nickname, Tumbledown Dick, and with good reason: he proved to be every bit as useless as his moniker suggests. He never quite made the grade and, after a period of chaos, the English parliament invited King Charles’s son back from his exile in France. Amid great celebrations, King Charles the Second was restored to the throne.

The new king was, understandably, still furious with the man who had signed his father’s death warrant and so one of the first things he did was to have Cromwell’s tomb in Westminster Abbey broken open. The body was removed and taken across town to the famous execution site of Tyburn, where London’s Marble Arch stands today.

But Richard was better known by his nickname, Tumbledown Dick, and with good reason: he proved to be every bit as useless as his moniker suggests. He never quite made the grade and, after a period of chaos, the English parliament invited King Charles’s son back from his exile in France. Amid great celebrations, King Charles the Second was restored to the throne.

The new king was, understandably, still furious with the man who had signed his father’s death warrant and so one of the first things he did was to have Cromwell’s tomb in Westminster Abbey broken open. The body was removed and taken across town to the famous execution site of Tyburn, where London’s Marble Arch stands today.

Thousands gathered to see

Cromwell’s body hanged from the gallows like a common criminal. At the end of

the day, it was cut down, the head was hacked off and the body dumped in a

common grave. Then a spike was hammered through the head and it was put on

public display on top of Westminster Hall, as a warning to anyone else who

might be tempted to challenge the Divine Right of the Royal House of Stuart.

You might think a severed head would rot away in no time. But Cromwell’s body had been embalmed before his burial (common practice for important people back then) and so the head proved remarkably robust at withstanding the elements. In fact, it remained on top of Westminster Hall for the best part of a quarter of a century.

And then, one night, it was blown down in a storm. Legend has it that it fell at the feet of the soldier standing sentry underneath who, for want of a better idea, put it under his cloak, took it home and hid it in his chimney. A rich reward for its return was posted and the whole of London searched for it. But in vain. The soldier kept his secret and only revealed the head’s location to his daughter on his deathbed.

It is assumed that the daughter made discreet enquiries and disposed of the head in a private sale because around ten years later, in 1710, it turned up in the collection of a man called Claudius de Puy who ran a private museum of curiosities, at the time of one London’s prime tourist attractions.

On de Puy’s death in 1738, the head disappears from the historical record for several decades, only re-surfacing in the 1770s in the possession of a failed comic actor and notorious drunkard called Samuel Russell. Russell displayed it at a little stall in a squalid tangle of alleys known as Clare Market (where the London School of Economics stands today) and in the evenings, he would show it off in the pub, where he would use it to act out scenes from Shakespeare before passing it around among his friends.

Eventually, Russell was forced to sell the head to pay off his debts and it ended up in the hands of some showmen called the Hughes brothers who thought they could make a few quid from it. They made it the centrepiece of an exhibition of Cromwelliana in London’s Bond Street in 1799, hoping to pull in a fashionable crowd paying top dollar for tickets. But almost nobody came, the exhibition closed and the brothers struggled for years to find a buyer for their expensive folly.

At last, in 1815, the head was sold to a private collector, a Mr Josiah Wilkinson of Kent - and it remained in the Wilkinson family for the next 145 years. The rest of the world took little interest in the family’s gruesome treasure during this time – and if anyone did, it was usually to question its authenticity. The celebrated historian, Thomas Carlyle, visited the family and was convinced that it couldn’t possibly be Cromwell, but most experts agreed that it almost certainly was. And then in 1958, it was inherited by a hospital doctor from Kettering called Dr Horace Wilkinson who decided that enough was enough.

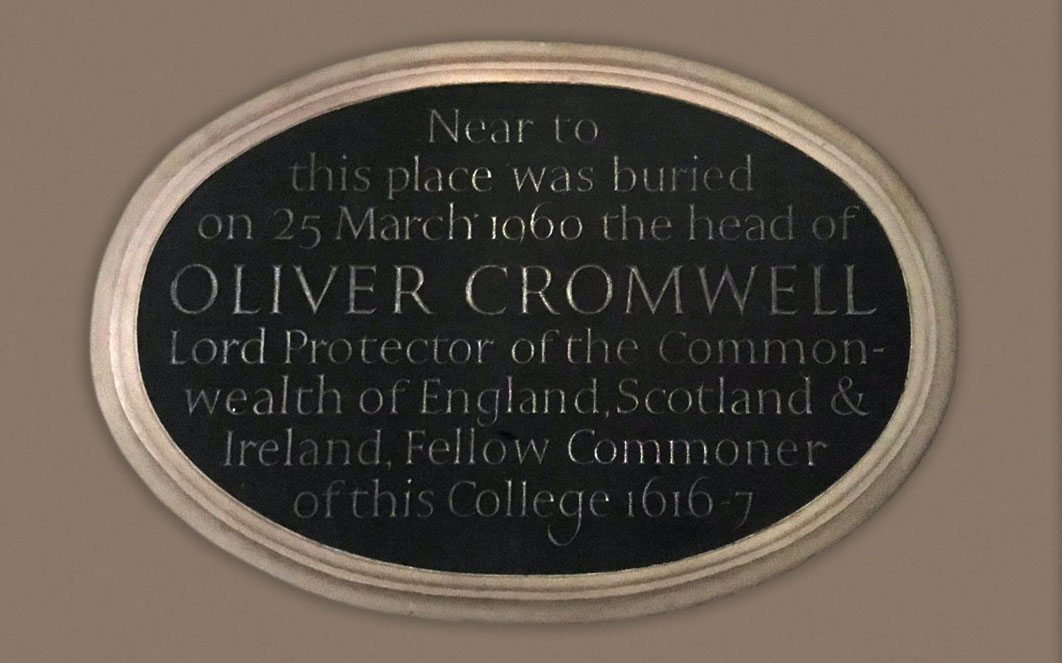

He contacted the powers-that-be at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, where Cromwell had studied as a young man. The good doctor suggested that it might be a suitable place for the head’s burial. The college agreed to his request, although one suspects they had mixed feelings. There was no public ceremony, the media were not informed and the burial spot went unmarked except for a plaque tucked away high up on the wall next to the inner door of the college chapel, which gave away no more than that the head was buried ‘Near to this place…’

And so Cromwell’s head was finally laid to rest over three hundred years after he died… or, er, maybe not so finally. According to Elgin Barrett, anyway.

Another quick hiss-torical note. The riot at the Garden House Hotel in Cambridge described in the story really did happen and it was indeed considered to be the most extreme British student protest of the era, with six students subsequently sent to prison for their role in it. There is still a hotel on the site – now the Five Star Doubletree Hilton – but it is not the same building as the old hotel which was demolished after being destroyed by a devastating fire in 1972.

And one more thing. I should also mention that the words spoken by the hissing head are all Oliver Cromwell’s own, taken from his speech dismissing the charmingly named Rump Parliament of 1653.

But as to the hiss-torical veracity of the rest of the tale… well, you’ll have to judge that for yourself.

You might think a severed head would rot away in no time. But Cromwell’s body had been embalmed before his burial (common practice for important people back then) and so the head proved remarkably robust at withstanding the elements. In fact, it remained on top of Westminster Hall for the best part of a quarter of a century.

And then, one night, it was blown down in a storm. Legend has it that it fell at the feet of the soldier standing sentry underneath who, for want of a better idea, put it under his cloak, took it home and hid it in his chimney. A rich reward for its return was posted and the whole of London searched for it. But in vain. The soldier kept his secret and only revealed the head’s location to his daughter on his deathbed.

It is assumed that the daughter made discreet enquiries and disposed of the head in a private sale because around ten years later, in 1710, it turned up in the collection of a man called Claudius de Puy who ran a private museum of curiosities, at the time of one London’s prime tourist attractions.

On de Puy’s death in 1738, the head disappears from the historical record for several decades, only re-surfacing in the 1770s in the possession of a failed comic actor and notorious drunkard called Samuel Russell. Russell displayed it at a little stall in a squalid tangle of alleys known as Clare Market (where the London School of Economics stands today) and in the evenings, he would show it off in the pub, where he would use it to act out scenes from Shakespeare before passing it around among his friends.

Eventually, Russell was forced to sell the head to pay off his debts and it ended up in the hands of some showmen called the Hughes brothers who thought they could make a few quid from it. They made it the centrepiece of an exhibition of Cromwelliana in London’s Bond Street in 1799, hoping to pull in a fashionable crowd paying top dollar for tickets. But almost nobody came, the exhibition closed and the brothers struggled for years to find a buyer for their expensive folly.

At last, in 1815, the head was sold to a private collector, a Mr Josiah Wilkinson of Kent - and it remained in the Wilkinson family for the next 145 years. The rest of the world took little interest in the family’s gruesome treasure during this time – and if anyone did, it was usually to question its authenticity. The celebrated historian, Thomas Carlyle, visited the family and was convinced that it couldn’t possibly be Cromwell, but most experts agreed that it almost certainly was. And then in 1958, it was inherited by a hospital doctor from Kettering called Dr Horace Wilkinson who decided that enough was enough.

He contacted the powers-that-be at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, where Cromwell had studied as a young man. The good doctor suggested that it might be a suitable place for the head’s burial. The college agreed to his request, although one suspects they had mixed feelings. There was no public ceremony, the media were not informed and the burial spot went unmarked except for a plaque tucked away high up on the wall next to the inner door of the college chapel, which gave away no more than that the head was buried ‘Near to this place…’

And so Cromwell’s head was finally laid to rest over three hundred years after he died… or, er, maybe not so finally. According to Elgin Barrett, anyway.

Another quick hiss-torical note. The riot at the Garden House Hotel in Cambridge described in the story really did happen and it was indeed considered to be the most extreme British student protest of the era, with six students subsequently sent to prison for their role in it. There is still a hotel on the site – now the Five Star Doubletree Hilton – but it is not the same building as the old hotel which was demolished after being destroyed by a devastating fire in 1972.

And one more thing. I should also mention that the words spoken by the hissing head are all Oliver Cromwell’s own, taken from his speech dismissing the charmingly named Rump Parliament of 1653.

But as to the hiss-torical veracity of the rest of the tale… well, you’ll have to judge that for yourself.

The story of Cromwell’s head is

told by many of Cromwell’s many biographers but nowhere better than in Jonathan

Fitzgibbon’s beautifully written book.